410

Views & Citations10

Likes & Shares

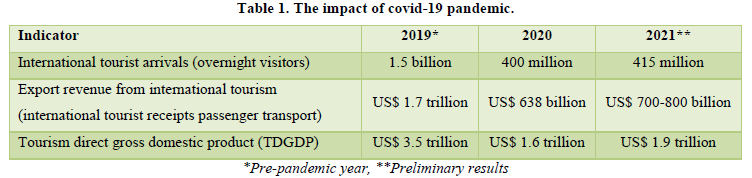

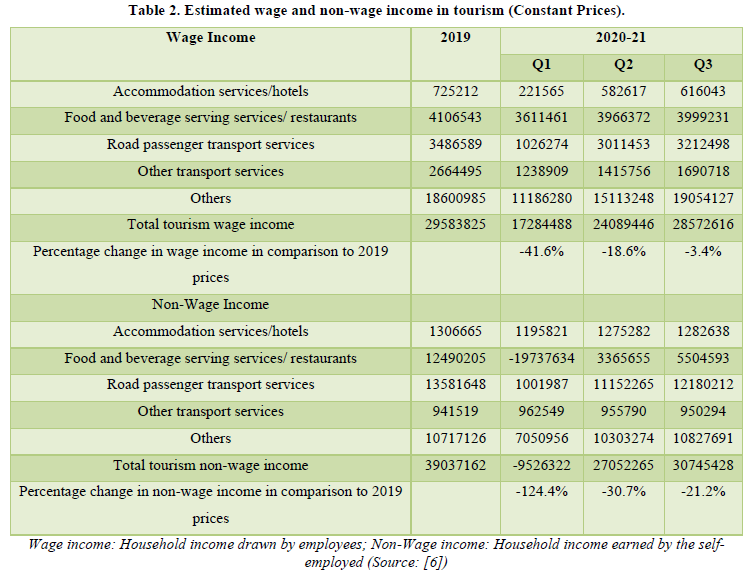

In India, the covid-19 pandemic resulted in a 66% decline in International Tourist Arrivals when compared to the previous year (TAN, 2020). The micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) was estimated to lose 21% of revenue with a margin of just 4-5% (Indrakumar, 2020). Amidst these losses, the sector which suffered a huge downturn was tourism and the services associated with it. Tourism accommodation can be termed as the most important service offered to a tourist. Its provision predominantly defines the status of tourism of a destination. It is a vital component as tourism can only flourish in the presence of adequate stay facilities. That being said, the covid-19 pandemic has brought about many challenges. This is more so in the case of small tourism accommodations such as bed and breakfast, homestays, lodges, guest houses, small resorts, etc. They are the ones who are enormously impacted by the sudden decline/stop in tourist flows. There was an immediate halt in revenue and earnings. In relation, (Table 2). portrays a bird’s eye view of the loss of wage income (i.e. income of employees working in the tourism sector) and non-wage income (i.e. salary of the self-employed or tourism business owners) in the first year of covid-19 pandemic in India. While wage income fell by a huge 41.6%, non-wage income nosedived by a massive 124.4% in the first quarter of the year 2020-21. As such, the labor-intensive tourism sector has had to experience major economic losses (Munjal, Siddiqui, Pratap, Alam,& Mukhopadhyay, 2021) and any full recovery will most likely take till the year 2023-24.

The response to the covid-19 pandemic came in the form of conditions and restrictions which are often referred to as ‘new normal measures. The essential lockdowns, quarantines and social distancing led to a stagnation of economic activities (Adam, Alarifi, 2021; Omar, Ishak, Jusoh, 2020; Oyewale, Adebayo, Kehinde, 2020). In particular, the small tourism accommodation has had to adapt and apply the new normal measures in an effort to return to business. The World Tourism Organization, (2000) defines them as businesses with less than 50 rooms, employing less than 10 people and primarily operating in the lower segments of the market. Being small enterprises, it is more critical to adequately apply the new normal measures for business continuity and stability. The assessment of host preparedness becomes crucial to reestablish trust and reinforce the desire of travel amongst tourist (Bonfanti, Vigolo, Yfantidou, 2021; Narmadha, Anuradha, 2022). On the other hand, the tourist experiences of the small tourism accommodation build confidence on the best practices and progress of the sector.

Accordingly, the study is focused on north-east India which comprises of eight states (Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim and Tripura) with an emphasis on Meghalaya and Assam. These two are considered in the assessment as they are emerging destinations of north-east India with potential for take-off in tourism activities. Meghalaya is primarily a nature-based tourism destination with promising leisure and adventure activities and Assam is predominantly features in terms of natural beauty, culture and wildlife.

LITERATURE REVIEW

New normal measures and the changes in service delivery

The disruption of covid-19 pandemic calls for the accommodation units to prioritize provision of satisfactory experience without compromising on safety (Bonfanti, Vigolo, Yfantidou, 2021). The focus should be on planning the customer experience and organizing the tangible and intangible elements of service delivery so as to ensure a memorable tourist experience. Narmadha, Anuradha, (2022) & Bonfanti, Vigolo, Yfantidou, (2021) identified seven measures for businesses to deliver safe experiences, namely, hygiene measures, internal work reorganization, staff training, reorganization of services cape, investments in digital technology, customer wait time reorganization and updated communication. In addition, new normal measures such as hand sanitizing, mask wearing, social distancing, etc. has changed the entire service delivery landscape. Today, QR codes instead of physical menus, contactless check-in and check-out, mobile app payments and app-based food ordering are solutions for small accommodation units (Hudson, 2020). Larger accommodations also make use of robots to disinfect rooms thereby allowing them to work with minimum capacity and maximum physical distancing (Seyitoğlu, Ivanov, 2020).

Small tourism accommodation

Small firms have traditionally dominated the tourism sector for a long time now (Buhalis 1996; Morrison, 1998). Globally, about 95% of the businesses are small enterprises (Lashley, & Rowson, 2006) and characterized by some uniqueness and heterogeneity in the way they operate. Notably, Morrison, (1998) points out that the researchers have defined small business in numerous ways. For most sectors, small firms are defined by its size in terms of turnover, number of employees, profitability, etc. In addition, the existing literature on tourism and hospitality also fails to provide a universal definition for small firms. Various authors have considered the number of bed spaces as synonymous to number of rooms. Nonetheless, it is acknowledged that the intangible and qualitative features should be considered in unison with the tangible and quantitative factors like rooms and employees in comprehending small tourism accommodation. As such, definitions vary from one country to another and from one research work to another depending on the aim of research (Ansah, 2014).

New normal measures and host preparedness

The need for reorganization and restrictions under the new normal measures will help small tourism accommodation to define a new normal with positive effects on customer experience. In general, the attention to hygiene and health conditions shall mold the decision-making process of tourist (Narmadha & Anuradha, 2022). Focusing on the likes and desires of consumers in this changing world would be the greatest deciding factor of business success. Keeping the new normal measures in mind, the business owners should explore new opportunities to escalate growth, connect with customers, build a sense of community, develop skill sets and most importantly learn to survive in a post-pandemic (Liguori & Pittz, 2020). By and large, it is no surprise that people wish to get back to doing things normally as was done before. However, the new normal is to live with Covid in a changed (Price, Wilkinson, Coles, 2022). The requirement of working from home can be deemed as an opportunity for small business owners to improve their performance (Zhang, Gerlowski, Acs, 2022) just as the adoption of digital tools for developing strategic, managerial and digital skills in order to increase efficiency (Audretsch & Belitski, 2021; Belitski, Guenther, Kritikos, Thurik, 2022).

Meurer, Waldkirch, Schou, Bucher, Lamp, (2022) state that all small businesses must be prepared for the new normal of a digitally driven economy. Therefore, it is the responsibility of the host to reestablish trust of their users through effective and increased communication. In tourism, the travel risk assessment by the tourist in times of uncertainty leads to the postponement or cancellation of the tour altogether. This ultimately has negative impacts on tourism. As a result, it is critical for the host to try to incorporate risk mitigation measures and ensure that social, environmental, and economic needs of their local communities are addressed in a post-pandemic world (Bratić, Radivojević, Stojiljković, Simović, Juvan, 2021). On the brighter side, the covid-19 pandemic could be seen as an opportunity for small tourism accommodation to revisit their past practices and come back better and stronger with a solid future plan while managing the crisis and mitigating its impact (World Tourism Organization, 2020).

New normal measures and tourist experiences

The perceived risk about covid-19 has induced travel anxiety causing tourists to shift their travel behavior (Bratić, Radivojević, Stojiljković, Simović, Juvan, 2021). Due to the prevailing scenario in the contemporary world, several new travel trends have emerged amongst tourists in the new normal era. It has completely changed the way of how people live and travel. Travelers today prefer sustainable destinations which are secluded in the lap of nature to satisfy their ecotravel, money value, private space, social distance, security, accessibility and cleanliness needs (Narmadha & Anuradha, 2022). There is a strong demand for immersive tours with short itineraries which takes heed of the underlying issues of financial stability, accessibility, facilities, health and safety of tourists. Hall ET, (1963) argued that spatial arrangements can affect people’s perceptions and therefore, social interaction level and physical distance all influence perception of risk. As an outcome, non-verbal communication constitutes a larger chunk of interpersonal communication. The use of appropriate non-verbal interactions influences a consumer’s behaviors and attitudes. In view of social distancing as a new normal measure, non-verbal form of communication may have profound impact on consumer experience which in turn induces satisfaction or dissatisfaction among customers (Lin, Zhang, Gursoy,2020). With the covid-19 pandemic, people’s inclination towards travel degraded. Nonetheless, an indication of experiencing safe travel by service providers can actually enhance revisit intention of tourists (Rahimizhian & Irani, 2021). Hence, delivering on a safe and secure tourist experience is a key for the revival of the tourism sector as a whole.

It is to be noted that since studies on tourist experiences under new normal measures is currently scarce, not much literature can be found. The current assessment aims to throw light on this aspect from the purview of small tourism accommodation and thereby contribute towards the literature and knowledge on the subject-matter.

OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY

The study aims at assessing the subject-matter of new normal measures from a two-fold perspective. Firstly, the preparedness of the host with regards to adopting and applying the new normal measures. Secondly, the tourist experiences in relation to the processes and procedures covering new normal measures. This is perceived as an important area of research as it encompasses small tourism accommodation which is an important element in tourism services.

The data and methods applied are aimed at assessing how the new normal measures are implemented and what are its implications with regards to the host who operate small tourism accommodation on one hand and the tourist experiences on the other. The scope of the study is host preparedness in the context of small tourism accommodation and tourist experiences in the states of Meghalaya and Assam of north-east India. These two states (from the eight states of north-east India) are an emerging tourism destination of the region. The period in focus covers the covid-19 pandemic (i.e. March, 2020 till present) with a particular emphasis on the current situation (the early part of the year 2022) in terms of the response of small tourism accommodation to new normal measures. Against this backdrop, the tourist experiences form as a basis for understanding and inference on the subject-matter of the study.

In relation to types of data, both secondary and primary data are used. The secondary data comprise of print and electronic publications from various sources and form the background of the study. The primary data was collected from December, 2021 to March, 2022 through field survey and interviews by using a schedule. The schedule applied an interval scale of 1 for ‘no’, 2 for ‘low’, 3 for ‘moderate’, 4 for ‘notable’ and 5 for ‘high’ emphasis on new normal measures by the host and the subsequent tourist experiences. The survey covered small tourism accommodation service providers and the tourist who had visited the two destinations of north-east India during the period. Two criteria were used for data. Firstly, the small tourism accommodation has been in existence prior to the covid-19 pandemic and currently lays emphasis on new normal measures. Secondly, the tourist stayed in the small tourism accommodation for a minimum duration of at least two days.

The total sample size used for assessment is 240. This is classified into two, namely, 80 samples for host preparedness (40 each from Meghalaya and Assam) and 160 samples for tourist experiences (80 each from Meghalaya and Assam). The samples were collected from the more popular tourism attractions of Meghalaya and Assam such as Sohra (also known as Cherrapunji), Shillong, Mawlynnong, Dawki, Shnongpdeng, Guwahati, Kaziranga, Tezpur, Sivsagar, etc. The small tourism accommodation covers homestays, resorts, guest houses and lodges. A ratio of 1:2 was used in the sampling for host preparedness and tourist experiences. This means for every host sample; two tourist experiences samples were collected. These tourists were the guest of the host sample considered. As such, the host was identified first and subsequently the tourists attached to a particular host.

The variables of the study include a holistic representation of new normal measures such as enforcing of regular hand sanitizing, hand washing, proper masking, social distancing practices, usage of ICT (information and communication technologies) for registration, check-in and contactless service delivery, changes in business processes, focus on frugality, etc. In addition, it comprises of profile variables such as gender, age, education, course/training on entrepreneurship, nature of travel, accommodation type, accommodation size, etc. The tools and techniques used involved descriptive statistics in case of profile related variables. In the case of host preparedness and tourist experiences variables, descriptive statistics including t-test was used for results and discussion on the subject-matter of new normal measures. The t-test used was ‘one sample test’ and the test value applied was 1 (one) representing a scale of ‘no’. The reason being before the covid-19 pandemic the small tourism accommodation was not practicing or required to practice the new normal measures. The scores derived for the variables were used to holistically comprehend host preparedness and tourism experiences through results and discussion. Further, the question of whether a course/training on entrepreneurship equips the host in mitigating the effects of covid-19 better as compared to the others was assessed. This was done by comparing the mean scores of the host who had undergone a course/training on entrepreneurship as against those who did not.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

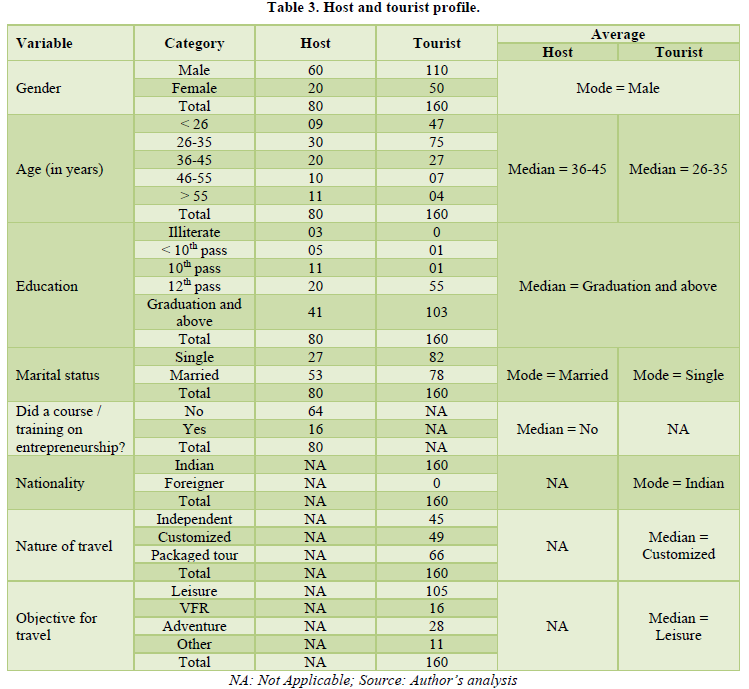

The analysis of the profile of the host and the tourist (Table 3) portrays a number of important insights. This table is meaningful as it forms as the basis for understanding how the stakeholders concerned reacted towards the new normal measures. The profile of the host and tourist is represented in terms of gender, age, education and marital status. For the tourist, nationality, nature of travel and objective for travel are also compiled. The host profile also includes an assessment of whether the operator of the small tourism accommodation had gone through a course/training on entrepreneurship in the past before the covid-19 pandemic. Overall, the profile proved the structural make-up of the respondents included in the study.

In the case of gender and education, the respondents for both host and tourist are mostly males with an educational qualification of graduation and above. This combination of gender and education acts as an important indicator for tourism positioning of north-east India. In terms of age and marital status, the host respondents are mostly in the age bracket of 36-45 years with the majority being married.

On the contrary, the tourist profile shows that they are primarily in the ages of 26-35 years and mainly single. It can be said that the north-east India tourism attractions are more oriented towards the younger generation. This can be corroborated with the fact that the tourist objective for travel is more oriented towards leisure and adventure. With regards to nationality of the tourist during the study period, all of them were Indians. This is more to do with the restriction that was still in place for foreign travel into India. The nature of travel mainly used by the tourist is customized with features of self-arrangements for travel and accommodation (independently done) with specialized services being used for booking of tourism activities such as adventure and recreation. On the subject-matter of course/training on entrepreneurship, the majority of the host responded in the negative. While this in itself represents as a challenge with regards to managing the nuances of covid-19, it also highlights that the small tourism accommodation in north-east India are in most cases owned, operated and managed by people who do not possess the desired skills set/training in business and entrepreneurship. This can be a pitfall when it comes to professional management and progress of the tourism accommodation.

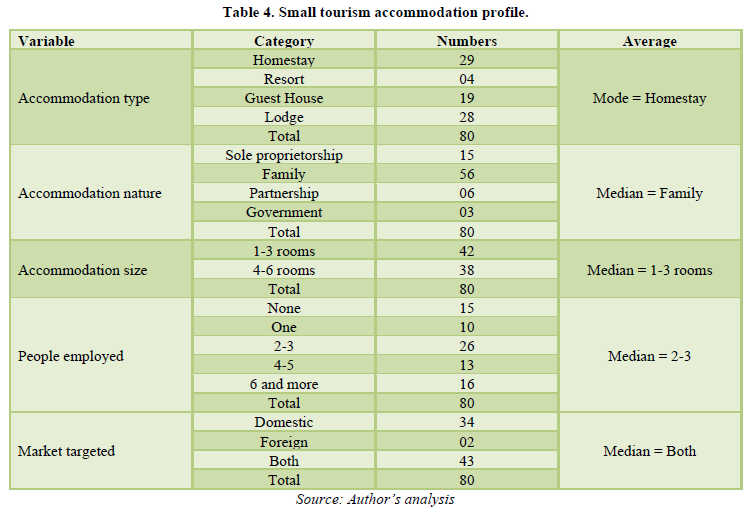

In continuation, Table 4 depicts small tourism accommodation profile in the context of accommodation type, accommodation nature, the size of the accommodation, the number of people employed and market targeted.

The profiling gives a picture of the features of small tourism accommodation and how it may relate with the new normal measures behavioral changes/patterns of the host with regards to responding to the challenges of covid-19 pandemic. At the outset, most of the small tourism accommodations are homestays and lodges. They offer a cozy and need-based accommodation as per the needs and wants of the tourist in terms of services. These accommodations are primarily family owned with a certain member entrusted with the management and operations of the enterprise. The tourism sector provides meaningful opportunities for livelihood. In north-east India, family business is more commonly used in taking advantage of the opportunities available. Being a more remote part of India and in keeping with the kind of services required in tourism, the majority of the tourism accommodations have ‘one to three’ rooms. However, the ‘four to six’ room accommodation also figures prominently. In general, the small tourism accommodation employs ‘two to three’ people for the provisions of services such as food and beverages, house-keeping, front-office, etc. In most cases, the front office is operated by the owner of the enterprise and they mainly target both the domestic and foreign tourist through their advertising, marketing and service offerings.

The assessment of host preparedness and tourist experiences with regards to new normal measures presents an interesting reading. It has the potential to underline how pandemic caused new normal measures can change the entire services cape of services offered. Similarly, the assessment of tourist experiences on the new normal measures offers valuable insights on the planning, strategy and implementation blueprints that may be applied by the small tourism accommodation. The Cronbach Alpha values of host preparedness and tourist experiences variables are 0.76 (N=14) and 0.71 (N=12) respectively. The data sets are reliable and meet the internal consistency needs. Accordingly, it is used for assessment and drawing of inferences on the new normal measures of small tourism accommodation of north-east India.

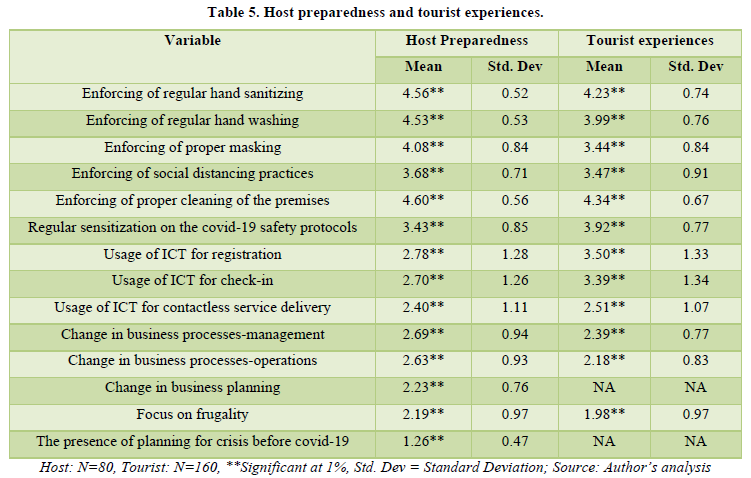

The new normal measures from the purview of host preparedness and tourist experiences are highlighted in Table 5.

The results highlight that both the host and the tourist returned a ‘moderate’ and ‘notable’ score on variables relating to hand sanitizing, hand washing, masking, social distancing practices, cleaning of the premises, sensitization on covid-19 safety protocols and the usage of information and communication technologies (ICT) for registration and check-in. For the host, the change in business processes with regards to management and operations also recorded a meaningful score. However, lower scores were seen in change in business planning, frugality and presence of planning for crisis before covid-19. For the tourist experiences, the lower scores are in the case of change in business processes (operations) and the focus on frugality. Overall, both the host and tourist have had to adapt as a result of the response to the challenges caused due to the covid-19 pandemic. The tourism sector as a whole had to assimilate and adjust to a number of new developments both in terms of new normal measures and the manner in which service is experienced by the tourist.

Tourist experiences are the outcome of host preparedness. The more detailed is the host preparedness, the more likely is a higher degree of involvement by the tourist with regards to the new normal measures. As such, the scores as derived in the case of tourist experiences is the result of host preparedness. How serious are the host in implementing measures to mitigate the effects of covid-19? This is the crux of the matter. In other words, if the host does not enforce any of the covid-19 protocols, the responses of the tourist would be redundant. Consequently, the host preparedness variables are classified into two categories for better understanding. The variables relating to hand sanitizing, hand washing, masking, social distancing, cleaning of premises and sensitizing on covid-19 safety protocols are classified as ‘externally enforced’ new normal measures. The remaining variables (from usage of ICT to presence of planning for crisis before covid-19) are classified as ‘internally enforced’ new normal measures.

Externally enforced basically refers to the new normal measures that are compulsorily to be implemented by the host in their small tourism accommodation. These are directed and advised by the health departments of Government of India and the state governments of Meghalaya and Assam. The outcome of these directions is the monitoring by the local authoritative bodies such as the district and locality administrations on the adherence to the covid-19 health and safety protocols. As a result, the hosts are to be sufficiently prepared and are to implement the guidelines without fail in their small tourism accommodation. This explains why the scores of host preparedness are on the higher side in case of these externally enforced variables. The covid-19 pandemic has resulted in a massive downturn in business. It resulted in revenue loss, income depreciation, reduction in standard of living and large-scale unemployment. These pressures entrusted a sense of responsibility towards following the externally enforced new normal measures so as to enable reopening of the tourism sector and the revival of livelihoods. The hosts were fully cooperative on the matter of following covid-19 rules and protocols. On the positive side, it is commendable that the accommodations did follow the guidelines on covid-19 and worked together in mitigating the challenges of the pandemic with the authorities.

The internally enforced is more to do with the internal business mechanisms of the small tourism accommodation. It mainly concerns planning, operations and management of the enterprise. In this case, the scores are more on the moderate and lower side. This highlights that the covid-19 pandemic has largely failed with regards to affecting a more robust and effective business practices. The small tourism accommodation will do what is enforced externally. However, it is not the same for internalities of the business. The new normal measures for ensuring business survival and creation of a more resilient organization are primarily not a focus of attention. The usage of ICT in business and operations and changes in management styles is critical as a new normal measure. Things are to be more closely monitored and evaluated on a continuous basis. The attention to these variables is not sufficient. In particular, there is a lack of focus on business planning before the pandemic. This is a serious problem area that needs to be reversed. An explanation for these developments is the lack of awareness and alertness on the needs and demands for business efficiency and effectiveness. There can be a lack of motivation as well. The requirement for creating a strong and resilient business enterprise through internal new normal measures has not registered with the host.

The tourist experiences on the ‘externally enforced and internally enforced’ new normal measures corroborate the same. Their experiences are more or less consistent with the host preparedness. They could experience a more robust enforcement of hand sanitizing, hand washing, proper masking and so forth. However, in relation to internally enforced new normal measures their experiences depict a need for better business practices and processes. This is needed so as to enable creation of a resilient small tourism accommodation. To this end, a larger focus is need on business processes (management and operations) and planning by the businesses for the long-term both on financial and non-financial needs and resources.

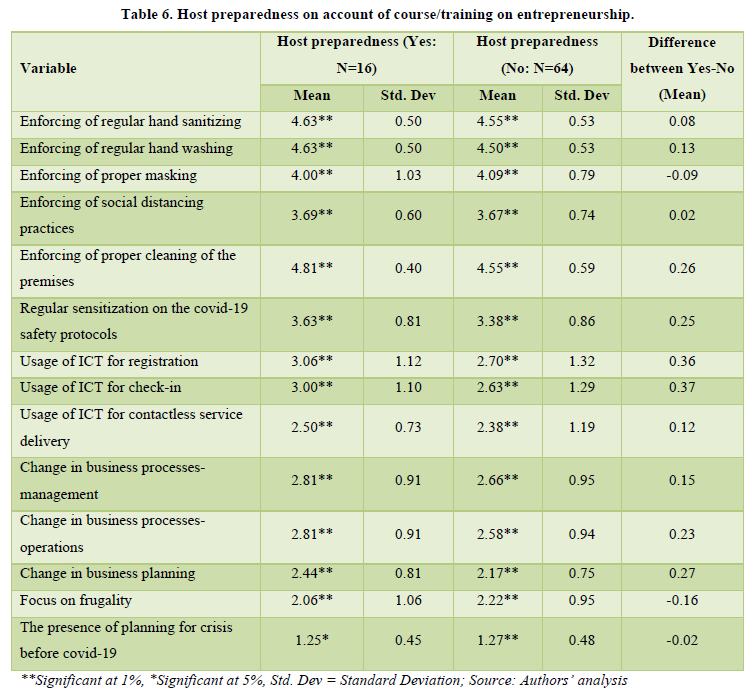

In dealing with the mitigation of the effects of covid-19, one question that arises is that of course/training on entrepreneurship. Studies indicate that an exposure to entrepreneurship training results in enhanced entrepreneur performance, molds entrepreneurial intentions, better self-alertness and self-efficacy through both active (hands on) and passive activities and opens up new horizons for participants to create a successful business (Almahry, Sarea, Hamdan, 2018; Ho, Uy, Kang, Chan, 2018; Lazear, 2005; OECD 2014). In the case of the current study, does such a course/training equip the host to face the challenges of a business downturn better as compared to others? An attempt has been made to answer this question by portraying host preparedness on the basis of whether the operator of the small tourism accommodation performs better on account of course/training on entrepreneurship (Table 6).

The results show that in the majority of the externally enforced and internally enforced new normal measures the host who had undergone a course/training performs better that the others. This shows that such an exposure helps equip the host to face the challenges like covid-19 pandemic more professionally. They are more innovative and alert to the need for change and modifying of their business processes. They are able to face the challenges more confidently and effectively. A larger difference is seen in the cases of sensitization on covid-19 safety protocols, usage of ICT for registration and check-in including change in business operations and planning. It is to be noted that amongst the host (N=16) who underwent a course/training on entrepreneurship, 10 of them were involved on a homestay business training and capacity building programme.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

The willingness of the host to respond during data collection was a limitation. In many instances, they were unwilling to share information and cooperate in the data collection process. The inhibition on their part had to do with the compulsory enforcement of the covid-19 protocols by the district and local administration. They were not willing to freely divulge information as they were apprehensive that it might fall into the hands of the governing bodies and as a result they might be subject to disciplinary action. To deal with this situation, data was collected only from the ones who were willing to provide information. However, even in this case the majority of the respondents were not willing to divulge information on revenue, expenses and profit. There was a lot of apprehension on this part. As an outcome of non-availability of data on these variables, they were no longer included in the assessment. In the case of tourist respondents, they were more cooperative and supportive on replying to the queries. Although the current study is focused on the small tourism accommodation alone, it has helped in deriving valuable insights into new normal measures. However, a larger study encompassing the other many verticals of the tourism sector such as transportation, eateries, large tourism accommodation, recreation and so forth would provide a more holistic picture of new normal measures with broader inferences.

CONCLUSION AND PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

The assessment highlights that the small tourism accommodation of north-east India have responded to the requirements of new normal measures appropriately both from the perspective of host preparedness and tourist experiences. The tourist experiences corroborate the efforts of preparedness by the host across all the variables. However, a greater emphasis is required in the case of ‘internally enforced’ new normal measures by the host. This is important for business continuity in case of future challenges and uncertainties like covid-19 pandemic. It is the basis of a strong and resilient business enterprise that would be capable of withstanding the sudden impacts of economic downturns. To this end, a focus on business education in general and entrepreneurship in particular can go a long way in achieving the objective.

In relation to policy, they are basically four-fold. Firstly, north-east India as a destination needs to market and position itself better to the domestic and foreign tourist. Factoring the younger age group that travel, it would be better if it positions itself as a leisure-adventure based tourism destination. Secondly, scaling of the small tourism accommodation into larger business enterprises is a must. It is the very basis of business growth and survival in the long-term. A supportive scheme from the government can be of benefit for the capable small tourism accommodation to expand. Thirdly, training and capacity building of the operators is required particularly in areas of internal business processes and management. The learned tourism stakeholders such as societies, NGOs and personalities can play a leading role in collaboration with the government. Lastly, a focus on entrepreneurship education at various levels (starting from schools) can help in imparting the requisite skills and motivate the capable/interested to involve themselves in business in a more professional and effective manner.

- Cucinotta D, Vanelli M (2020). WHO declares Covid-19 a pandemic. Acta bio-medica: AteneiParmensis, 91, 157-160.

- World Health Organization (2020). Coronavirus disease (Covid-19) pandemic. Available online at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

- World Travel and Tourism Council (2020). Travel and tourism - global economic impact & trends. London United Kingdom.

- TAN (2020). Foreign tourist arrivals to India tumble over 66% in March owing to coronavirus pandemic. Available online at: https://travelandynews.com/foreign-tourist-arrivals-to-india-tumble-over-66-in-marchowing-to-coronavirus-pandemic/

- Indrakumar D (2020). Covid-19 and its impact on micro, small and medium enterprises in India. Manpower Journal, LIV (3-4): 1-14.

- Munjal P, Siddiqui KA, Pratap D, Alam A, Mukhopadhyay D (2021). India and the coronavirus pandemic Economic losses for households engaged in tourism and policies for recovery. In A. Mehta (Eds.), National Council of Applied Economic Research, New Delhi.

- Adam N, Alarifi G (2021). Innovation practices for survival of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in the Covid-19 times the role of external support. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 10.

- Omar ARC, Ishak S, Jusoh MA (2020) The impact of Covid-19 movement control order on SMEs’ businesses and survival strategies. Geografia-Malaysian. Journal of Society and Space, 16, 90-103.

- Oyewale A, Adebayo O, Kehinde O (2020). Estimating the impact of COVID-19 on small and medium scale enterprise Evidence from Nigeria. pp: 1-19.

- World Tourism Organization (WTO) (2000). Marketing Tourism Destinations. WTO Business Council.

- Bonfanti A, Vigolo V, Yfantidou G (2021).The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on customer experience design The hotel managers perspective. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 94, 102871.

- Narmadha V, AnuradhaA (2022). Paradigm change in tourist preferences towards evolving new normal tourism and travel trends. Handbook of Research on Changing Dynamics in Responsible and Sustainable Business in the Post-Covid-19 Era IGI Global USA pp: 406-418.

- HudsonH (2020). Despite devastating blow covid19 gives tourism industry a chance to redeem itself. Available online at: https://fipra.com/update/despite-devastating-blow-covid19-gives-tourism-industry-a-chance-to-redeem-itself/

- Seyitoğlu F, Ivanov S (2020). A conceptual framework of the service delivery system design for hospitality firms in the post viral world. The role of service robots. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 91, 102661.

- Buhalis D (1996). Enhancing the competitiveness of small and medium sized tourism enterprises. Electronic Markets, 6, 1-6.

- Morrison A (1998) Small firm statistics A hotel sector focus. The Service Industries Journal, 18, 132-142.

- Lashley C, Rowson B (2006). Chasing the dream Some insights into buying small tourism accommodation businesses in Blackpool. CAUTHE Research Conference proceedings Melbourne Victoria.

- Ansah JM (2014) Small tourism accommodation business owners in Ghana: A factor analysis of motivations and challenges. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure. 3.

- Liguori E, Pittz T (2020). Strategies for small business: Surviving and thriving in the era of Covid-19. Journal of the International Council for Small Business, 1, 106-110.

- Price S, Wilkinson T, Coles T (2022). Crisis How small tourism businesses talk about COVID-19 and business change in the UK. Current Issues in Tourism, 25, 1088-1105.

- Zhang T, Gerlowski D, Acs Z (2022). Working from home Small business performance and the COVID-19 pandemic. Small Business Economics, 58, 611-636.

- Audretsch DB, Belitski M (2021). Knowledge complexity and firm performance Evidence from the European SMEs. Journal of Knowledge Management, 25, 693-713.

- Belitski M, Guenther C, Kritikos AS, Thurik R (2022) Economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on entrepreneurship and small businesses. Small Business Economics, 58, 593-609.

- Meurer MM, Waldkirch M, Schou PK, Bucher EL, Lamp KB (2022). Digital affordances: How entrepreneurs access support in online communities during the Covid-19 pandemic. Small Business Economics, 58, 637-663.

- Bratić M, Radivojević A, Stojiljković N, Simović O, Juvan E, Lesjak (2021). Should I stay or should I go Tourists’ Covid-19 risk perception and vacation behavior shift. Sustainability Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute, 13, 3573.

- World Tourism Organization (WTO) (2020). Impact assessment of the Covid-19 outbreak on international tourism. Available online at: https://www.unwto.org/impact-assessment-of-the-covid-19-outbreak-on-international-tourism

- Hall ET (1963) A system for the notation of proxemic behavior. American Anthropologist 65, 1003-1026.

- Lin H, Zhang M, Gursoy D (2020) Impact of nonverbal customer-to-customer interactions on customer satisfaction and loyalty intentions. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32, 1967-1985.

- Rahimizhian S, Irani F (2021) Contactless hospitality in a post-Covid-19 world. International Hospitality Review, 35, 293-304.

- Almahry FF, Sarea AM, Hamdan AM (2018) A review paper on entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurs’ skills. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 21.

- Ho MHR, Uy MA, Kang BNY, Chan KY (2018). Impact of entrepreneurship training on entrepreneurial efficacy and alertness among adolescent youth. Frontiers in Education, 3.

- Lazear EP (2005). Entrepreneurship. Journal of Labor Economics, 23, 649-680.

- OECD (2014). Job creation and local economic development OECD Publishing Paris.